InstructGPT#

Note

Making language models bigger does not inherently make them better at following a user’s intent. For example, large language models can generate outputs that are untruthful, toxic, or simply not helpful to the user. In other words, these models are not aligned with their users. In this paper, we show an avenue for aligning language models with user intent on a wide range of tasks by fine-tuning with human feedback.

High-level methodology#

Dataset#

Our prompt dataset consists primarily of text prompts submitted to the OpenAI API. We heuristically deduplicate prompts by checking for prompts that share a long common prefix, and we limit the number of prompts to 200 per user ID. We also create our train, validation, and test splits based on user ID. To avoid the models learning potentially sensitive customer details, we filter all prompts in the training split for personally identifiable information (PII).

To train the very first InstructGPT models, we asked labelers to write prompts themselves.

From these prompts, we produce three different datasets used in our fine-tuning procedure. The SFT dataset contains about 13k training prompts (from the API and labeler-written), the RM dataset has 33k training prompts (from the API and labeler-written), and the PPO dataset has 31k training prompts (only from the API).

Models#

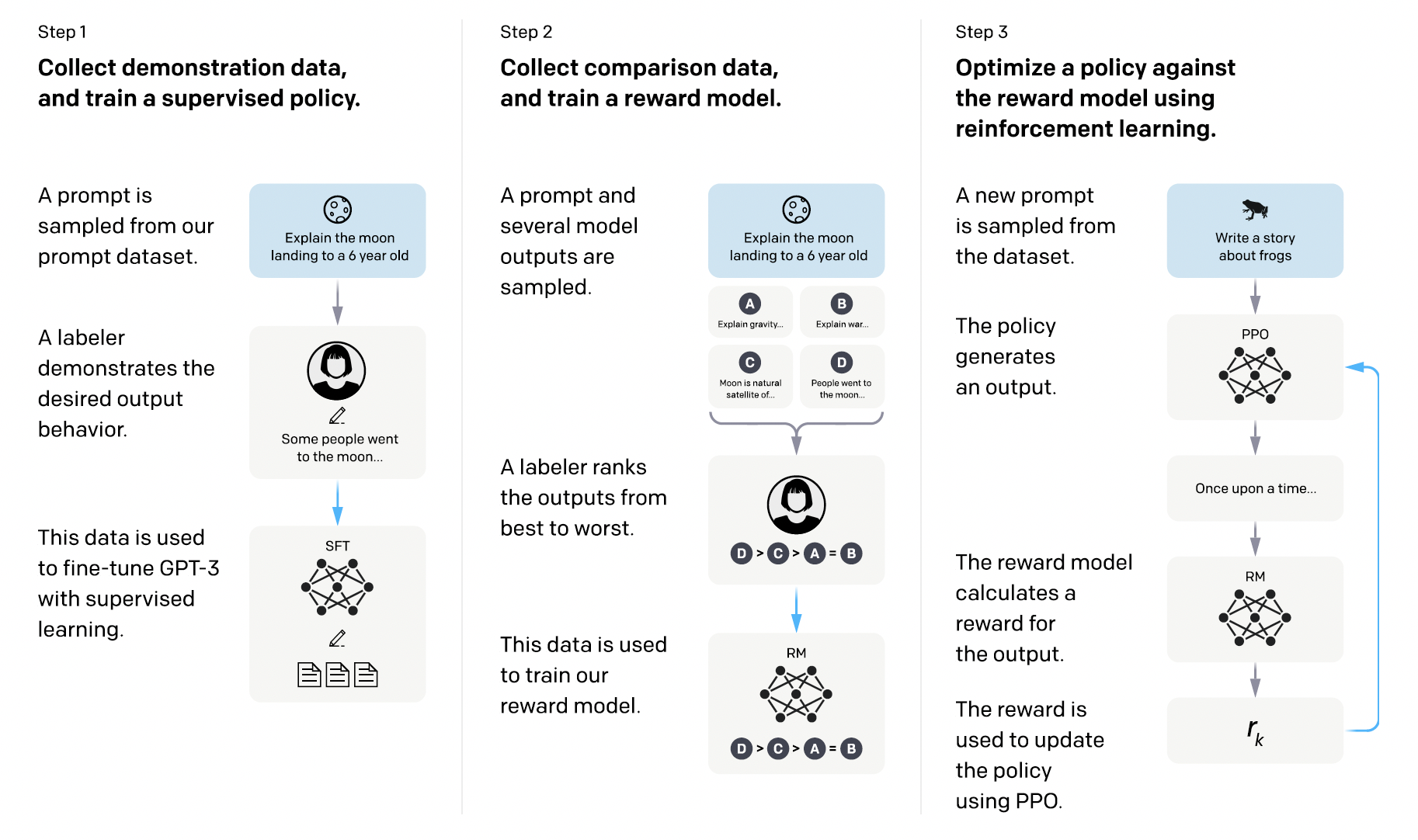

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT). We fine-tune GPT-3 on our labeler demonstrations using supervised learning.

Reward modeling (RM). Starting from the SFT model with the final unembedding layer removed, we trained a model to take in a prompt and response, and output a scalar reward.

In order to speed up comparison collection, we present labelers with anywhere between \(K=4\) and \(K=9\) responses to rank. This produces \(\binom{K}{2}\) comparisons for each prompt shown to a labeler. We train on all \(\binom{K}{2}\) comparisons from each prompt as a single batch element.

The loss function for the reward model is:

where \(r_{\theta}(x, y)\) is the scalar output of the reward model for prompt \(x\) and completion \(y\) with parameters \(\theta\), \(y_{w}\) is the preferred completion out of the pair \(y_{w}\) and \(y_{l}\), and \(D\) is the dataset of human comparisons.

Tip

We employ the Bradley-Terry model for pairwise comparison of competitors, where the strength parameter for \((x, y)\) is set to \(\exp(r(x, y))\). Then:

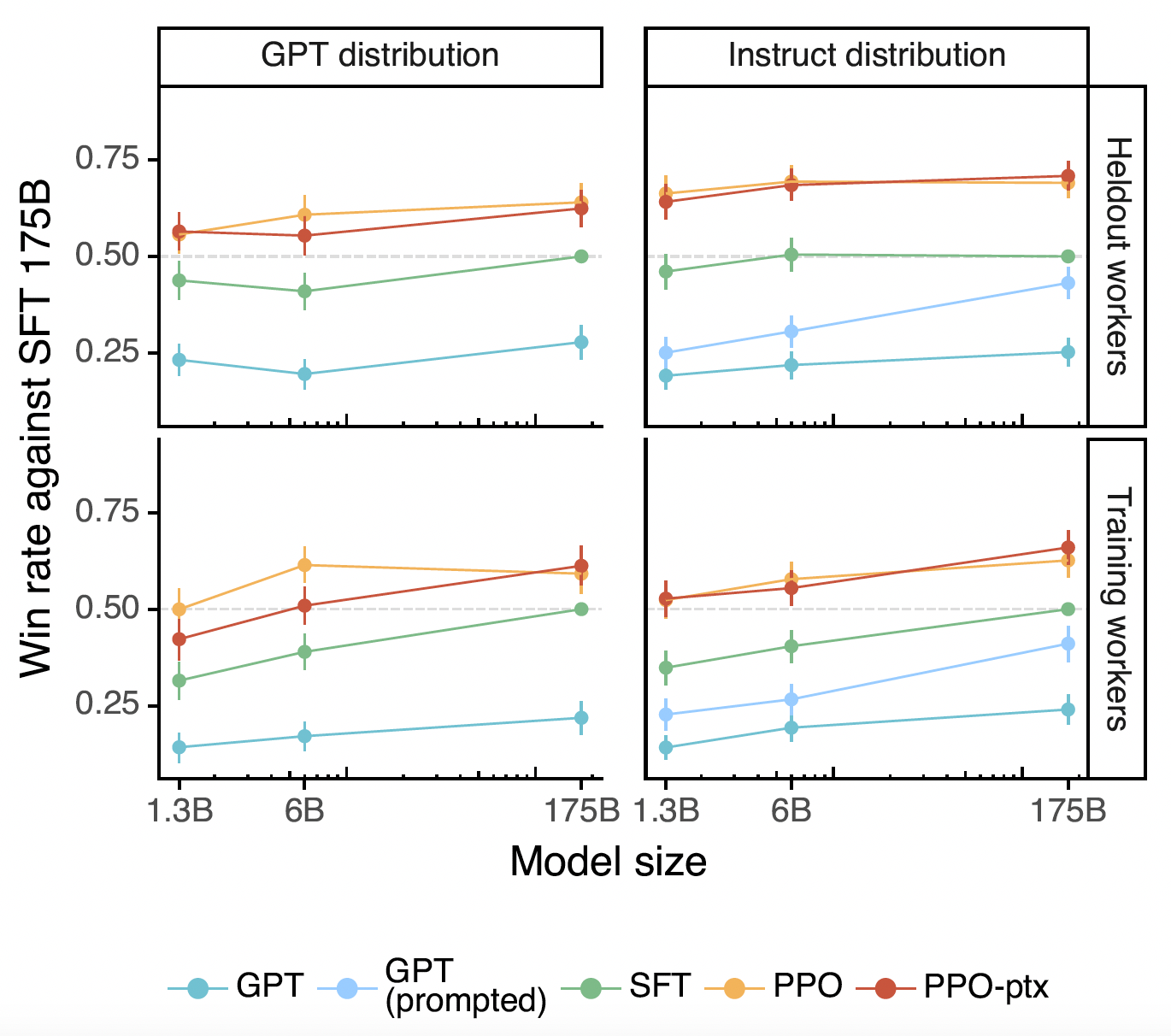

Reinforcement learning (RL). We fine-tuned the SFT model on our environment using PPO. Given the prompt and response, the reward model produces a reward and ends the episode. In addition, we add a per-token KL penalty from the SFT model at each token to mitigate over-optimization of the reward model. The value function is initialized from the RM. We call these models “PPO.”

We also experiment with mixing the pretraining gradients into the PPO gradients, in order to fix the performance regressions on public NLP datasets. We call these models “PPO-ptx.” We maximize the following combined objective function in RL training:

where \(\pi_{\phi}^{\text{RL}}\) is the learned RL policy, \(\pi^{\text{SFT}}\) is the supervised trained model, and \(D_{\text{pretrain}}\) is the pretraining distribution. The KL reward coefficient, \(\beta\), and the pretraining loss coefficient, \(\gamma\), control the strength of the KL penalty and pretraining gradients respectively.

Tip

For an event \(X\) with probability \(p\), it’s self information is

The less probable an event is, the more surprising it is and the more information it yields. The term

can be interpreted as our relative surprise. The KL divergence between \(P\) and \(Q\) is

can be interpreted as the expected relative surprise from using \(Q\) instead of \(P\) when the actual distribution is \(P\). It measures how one probability distribution \(P\) is different from the reference probability distribution \(Q\).

Tip

The implementation details of PPO can be found in this blog.

Results#