Concise Reasoning via Reinforcement Learning#

Note

In this work, we revisit the

core principles of reinforcement learning (RL) and, through mathematical analysis,

demonstrate that the tendency to generate lengthy responses arises inherently from

RL-based optimization during training.

We show that introducing a secondary phase of RL training,

using a very small set of problems, can significantly reduce chains of thought

while maintaining or even enhancing accuracy.

Response Length vs. Accuracy#

Tip

In both reasoning and non-reasoning models, with or without RL training, brevity and accuracy are strongly correlated. A related explanation for why long responses may reduce accuracy is the notion of deadends. In practice, deadends still occur in LLMs despite strong sampling techniques, often appearing as endless repetition.

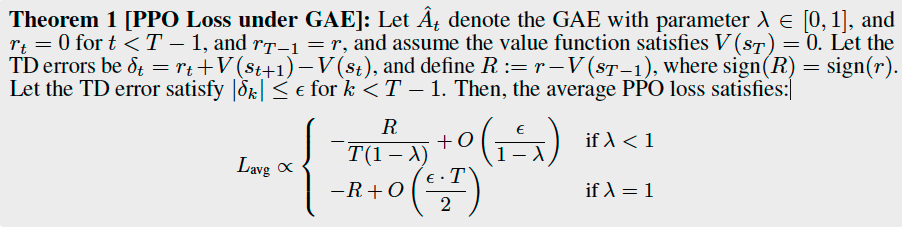

PPO Impact on Response Length#

For \(\lambda < 1\)

If \(R<0\): with high probalility \(L_{\text{avg}}\) decreases as \(T\) increases, so PPO favors longer responses.

If \(R>0\): with high probalility \(L_{\text{avg}}\) decreases as \(T\) decreases, so PPO favors shorter responses.

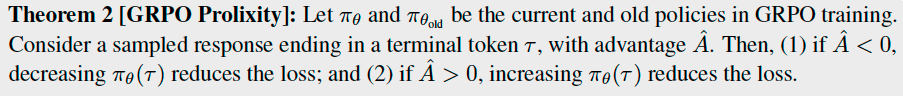

GRPO Impact on Response Length#

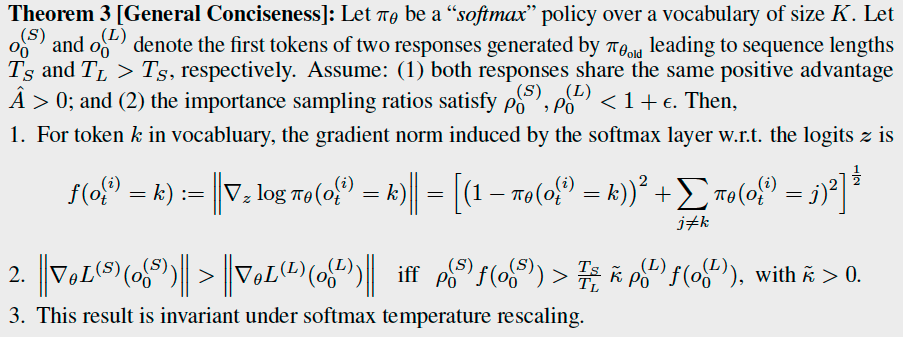

This result shows that \(\hat{A}<0\) is a sufficient condition for encouraging longer responses, a phenomenon widely observed by practitioners. When \(\hat{A}>0\), it implies a higher chance of termination at the current position once updated, but it does not favor shorter responses among multiple correct completions. To address this, we present a general result, mainly relevant to GRPO, focusing on what happens when two correct responses differ in length.

where

Under similar conditions (i.e., when \(\pi_{\theta}(o_{0}^{(S)}) = \pi_{\theta}(o_{0}^{(L)})\) and \(\rho_{0}^{(S)} = \rho_{0}^{(L)}\)), the inequality generally holds because \(\frac{T_{S}}{T_{L}} < 1\); hence, the shorter response receives stronger reinforcement.

The update almost surely favors shorter responses when \(T_S \gg T_L\), or \(\rho_{0}^{(S)}f(o_{0}^{(S)}) \gg \rho_{0}^{(L)}f(o_{0}^{(L)})\).

The Collapse of GRPO

\(\hat{A} = 0\) whenever the group is entirely correct or entirely incorrect.

Unsolvable problems: Theorem 2 does not apply and the loss is dominated by the KL term, which discourages deviation from the base model.

Fully solvable problems: A similar failure mode arises when problems are consistently solvable. As accuracy hits 1, the estimated advantage \(\hat{A}\) converges to zero, causing the policy loss to vanish. In this regime, the KL divergence term once again dominates the loss.

A Two-Phase Reinforcement Learning Strategy#

Our analysis highlights that when models are trained on exceptionally difficult problems, response length tends to increase, as longer outputs are more likely to reduce the loss amid predominantly negative rewards.

Tip

The key point is that verbosity is a consequence of RL minimizing its loss in the face of negative rewards, and it is this verbosity that may occasionally lead to improved accuracy, which then would be reinforced.

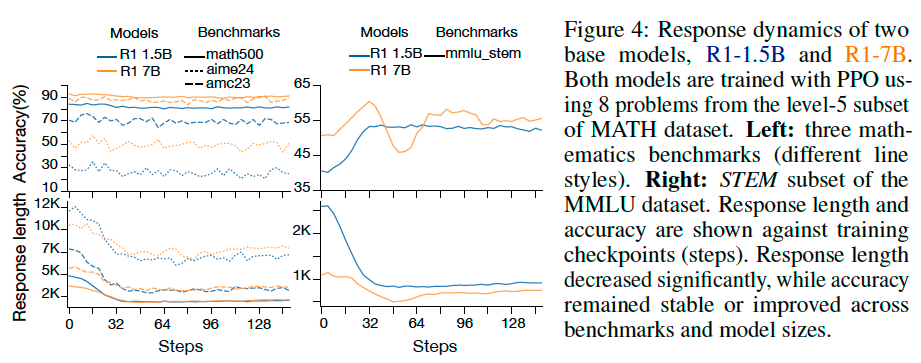

We propose a novel approach: enforcing conciseness through a subsequent phase of RL training with a dataset of occasionally solvable problems.

Normal RL training.

Training continues on problems with non-zero \(p_a\) (occasionally solvable). This phase enforces conciseness while preserving or even enhancing accuracy.

Experimental Results#

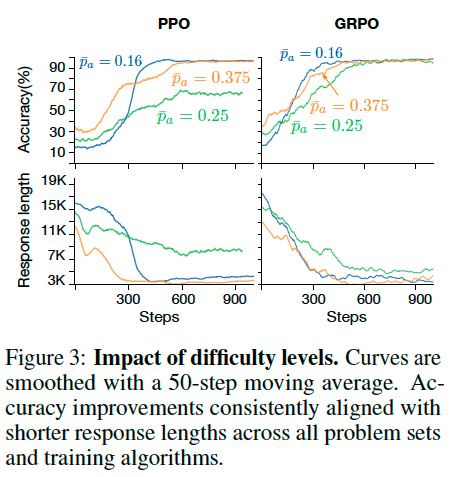

Impact of Problem Difficulty on Accuracy-Length Correlation

Decrease in Response Length